Review: Electric Dreams at Tate Modern

On being impressed by this tech-led exhibition at Tate Modern and why it’ll be a long time before artificial intelligence takes the place of artists

I am a self-confessed tech junky. I love technology. So Tate Modern’s Electric Dreams exhibition – looking at the intersection of art and technology in the pre-internet age – sounded perfect for me.

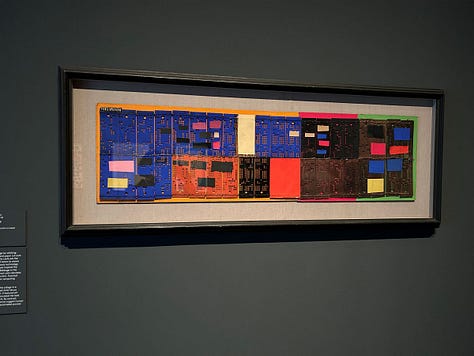

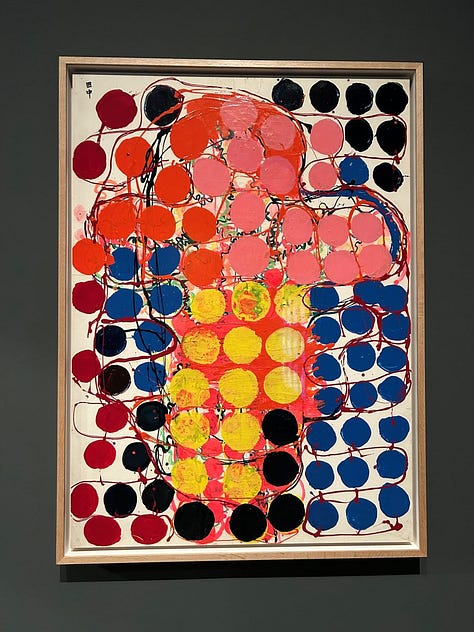

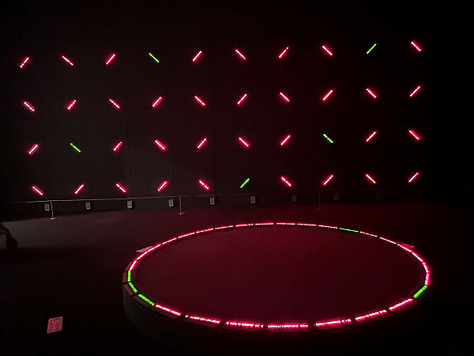

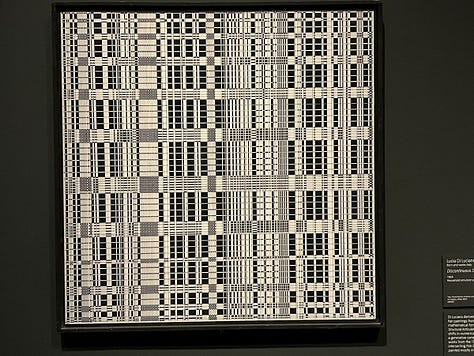

This major exhibition features artists who engage with science, technology and material innovation. They use technology to inform their work, experimenting with machine art and early home computers to automatically generate repeating patterns and sensory installations.

I could describe some of my favourite pieces in the exhibition, like Environnement Chromointerférent by Carlos Cruz-Diez, an immersive installation that projects constantly moving light and colour onto a series of objects that the observer can walk around and interact with. The projections change the appearance of both object and observer.

When I visited, a class of schoolchildren were enthusiastically engaging with the balls and cubes that make up the work, becoming part of the art themselves.

Emotional reactions

But I’ve recently decided that I don’t want to just describe what I see at exhibitions; I want to explore my emotional reactions to them. I first did this with Tate Modern’s Zanele Muholi exhibition. My reaction to this exhibition was so very different from Muholi.

Art and emotions: Zanele Muholi at Tate Modern

I visited the Zanele Muholi exhibition at Tate Modern at the beginning of January. I’d never heard of Zaneli Muholi and wouldn’t have known about this exhibition had I not visited the gallery previously and spotted a poster for this show. It looked interesting so I decided I’d come along. The exhibition closed on 26 January, so I knew I had to get there…

Electric Dreams was fun. I was entertained. But I wasn’t moved in the way I was with Muholi’s work. However, I did connect with the works. They fascinated me and appealed to me – especially the repeating patterns. These reminded me of the screensavers from the 90s that were infinite labyrinths or expanding networks of 3D pipes. I miss those.

I was impressed with the works on a technical level. I enjoyed how the artists had used technology to inform their work or made technology itself an artwork. I loved the vintage Ataris and the fictional videogame stills with their 90s-style blocky graphics which reminded me of a text adventure my older brother programmed way back when.

What is art?

This exhibition feels very timely, coming now when computer art is back in the headlines due to AI-generated imagery by the likes of ChatGPT and Bing’s Copilot. I’ve used pictures generated by ChatGPT for this newsletter. And they’re surprisingly accurate.

Are they art, though? In a few years time will anyone be able to generate an image by giving an AI a few instructions and call themselves artists? Will AI programmes be described as artists? Will people stop paying designers and instead use these (currently free) AI generators?

This last might seem likely. Paying a real live designer is costly, after all, and companies are much more interested in the bottom line than good design. The individuals working in those companies might baulk at using AI rather than a designer, but when the pressure is on to cut costs and stick to budgets, it’s going to be increasingly difficult to continue to justify paying a human.

However, I remember when spelling and grammar checkers were supposed to put paid to sub-editors and proofreaders. That didn’t happen. So maybe this won’t either.

Clever, not good

The images that ChatGPT generated for me are very clever. They work very well with the posts I needed them for. You could say that ChatGPT nailed the design brief. But they’re not very, well, good. Not as art or as design. They’re generic, they’re dull. They don’t move you, they don’t connect on an emotional level the way good art does, or even good design.

They look like what they are: an image generated from millions of possible images using keywords and search terms. An image created by an algorithm. There’s nothing creative or innovative about them. There was no intention behind their creation. Much the same as a short story pulled together by ChatGPT.

People like me, who would never have the money to pay a designer anyway, will use AI (although I’ll always prefer to take my own photos). But for those companies that rely on good design, it’s going to be a long time before ChatGPT can take the place of a real designer. Climate breakdown will have put an end to us all before then.

Something missing

There’s a lot of talk about how AI is going to save humanity, destroy humanity, take over the world, enslave us all (be nice to Siri, people!), free us from the chains of work so we can spend our lives in creative endeavours, take over all creative endeavours and condemn us to lives of drudgery. And so on and so on.

I’ve seen no real evidence that AI will do any of this, and if it does, it’s a long way away. AI’s creators might like to think that their invention is the artist of the future, but I’m not convinced. And the AI-generated images that I’ve seen so far won’t change my mind on that.

Of course, this might change as the technology moves on, but so far I think something essential is missing from AI’s attempts at art and that’s conscious intent. All it’s doing is generating a generic image from what it trawls from the internet.

Something I do think will happen, though, is that artists will incorporate AI imagery into their own work. Because humans, unlike machines, are infinitely creative. How they use AI remains to be seen – but if there’s anything that Electric Dreams shows us, it’s that artists can and will find inspiration anywhere.

The exhibition is still on at Tate Modern if you want to check it out. It runs till 1 June.