Art and emotions: Zanele Muholi at Tate Modern

Not a review: when I went to see this exhibition of works by the South African artist and activist I wanted to record my emotional reaction to it rather than what was on display

I visited the Zanele Muholi exhibition at Tate Modern at the beginning of January. I’d never heard of Zaneli Muholi and wouldn’t have known about this exhibition had I not visited the gallery previously and spotted a poster for this show. It looked interesting so I decided I’d come along. The exhibition closed on 26 January, so I knew I had to get there this month.

I’ve written exhibition reviews previously for this Substack but I wanted to try something different. Instead of just describing what was there, I wanted to think about how it made me feel.

Surely this would be more interesting, but also more challenging. I know from my own experience that art makes me feel ‘something’. I’m just not necessarily aware of what that something is.

So for this exhibition I deliberately paid attention to what I was feeling when I was looking at the artworks. I wanted to really understand the emotions that it provoked in me.

About the artist

Zanele Muholi is a South African artist. They’re non-binary. Working in photography, sculpture and installation, they describe themselves as a ‘visual activist’ rather than an artist. This exhibition is a collection of photography and sculpture that documents and celebrates the lives (and deaths) of South Africa’s LGBTQIA+ community.

In some ways this felt like completely the wrong exhibition for this exercise: it was going to provoke a lot of emotion. On the other hand, it felt like the ideal place for it: it was going to provoke a lot of emotion.

Writing about emotions, about how things make us feel, is difficult. Much of the time we lack the words, we simply don’t know how to express our emotions. That’s partly the reason for writing this – to find the right vocabulary.

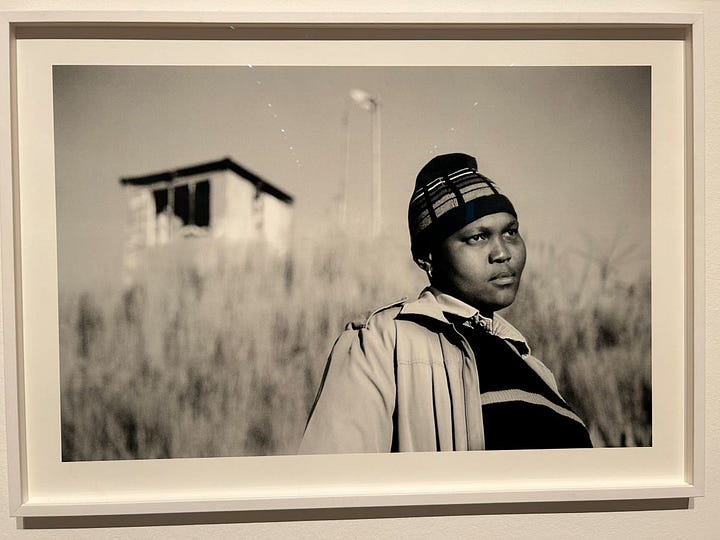

The photography was incredibly powerful. Largely black and white portraits, there was a raw honesty about the works that affected me. The subjects aren’t professional sitters or those used to posing for photographs, just ordinary people who have had extraordinary experiences.

South Africa’s 1996 constitution was the the first in the world to outlaw discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. Yet the country’s LGBTQIA+ community is still a target for violence, discrimination and even death.

People power

What struck me on entering the first room was the power of the subjects’ gazes – there was something unflinching, uncompromising about the way they stared directly at the camera, and therefore the viewer.

These are people whose lives are in danger just by existing. Yet they’re not hiding, not trying to be something or someone they’re not. Their very existence is defiance.

At the same time I felt displaced – like I shouldn’t have been there. I felt like these people’s lives aren’t something I should be privy to. As someone who’s straight, white, cis, their lives are not for my gaze. I wonder, is this sense of displacement something they experience in spaces where my experience is centred?

One portrait, of Busi Sigasa, hangs next to her poem, Remember Me When I’m Gone (scroll down for an image of Busi and her words). Busi was a victim of ‘corrective rape’, the rape of lesbians to ‘cure’ them of their sexuality. Because HIV is so prevalent in South Africa, many of the women contract the illness, as well as having to live with the attack.

Busi died in 2007. Her words are devastating, as is a series of portraits of other survivors of corrective rape. There’s also a series documenting another act of violence against LGBTQIA+ people: forcing a tyre over their heads and around their necks and then setting fire to it.

Language left me

And this is where language fails me. Because how can mere words communicate how this makes me feel? Horror, anger, despair – all of these things. But more than that – there’s a visceral, physical ache in my chest that I don’t have words to convey.

How can people do this to other people? There are tears in my eyes as I type this and I can’t begin to imagine what’s like for those people who live in fear of this happening to them.

But there is joy, defiance and beauty in this exhibition, too. A series of photos celebrating lesbian couples is beautiful. These photos are in colour and they express love, vulnerability and a sense of belonging. Just posing for these photos is an act of bravery and the subjects’ strength is impressive.

There’s also a series depicting drag queens and trans winners of beauty pageants. Again, these people’s very existence is an act of defiance and there’s a joyfulness and playfulness to these portraits that lifts my heart.

We must acknowledge the horrific things that happen LGBTQIA+ people in South Africa and beyond, and this exhibition goes a long way towards doing that. But we must also celebrate trans and queer joy, and this exhibition does a good job of that too.